Conducting Research

When engaged in rhetoric (the art of persuasion), it’s one thing to say, “This is what I think,” and another thing entirely to say, “This is what someone who is fully qualified to speak authoritatively on this issue thinks, and I heartily agree.” The use of evidence, or appeals to authorities other than yourself, improves your persuasiveness. In the sections below, we’ll walk through the process of conducting research to gather evidence and then use it in your speeches.

The Research Process

There are two general ways of conducting research:

- Breadth First

Get as broad an understanding about your subject as possible, from a wide variety of sources, so you understand the big picture before diving into any details.

- Depth First

Dig deep into the details of one particular thing to understand it inside and out before looking into the next thing.

The first tends to be what you do when researching for Platform Speeches and Debates. In those cases, building your broad understanding is the first step, but as you learn more about your topic, you’ll quickly realize that there is far more to talk about than can fit into the time you have for your speech. That’s when you start to narrow down on what it is you really want to focus on, and dig deeper in those particular areas. As you gather more evidence, you’ll be able to speak to a few key areas in detail, while at the same time relating them back up to the overall picture so your audience understands how everything fits in context.

The second tends to be what you do for Limited Preparation Speeches, where your topic is often already very narrowly defined. You’ll need to be able to dig in and answer the question directly with plenty of detail, so find all the evidence you can about that first. However, it’ll be beneficial to help your audience understand how your topic relates to the bigger picture of life, the universe, and everything, so after you’ve dug deep, you’ll want to come up to the top level to build your understanding of the broader context.

Where to Find Information

So you’ve already selected a topic, or you’ve had one assigned to you, and now you need to figure out what you’re going to say about it. Where do you start? The answer is it depends on what kind of information you’re looking for. If you’re looking for general background material in a topic area, your first bet might be a good old fashioned library. If you don’t want to make the trip, apps like Hoopla and Libby allow you to access your local library’s resources digitally. You’ll also likely find it beneficial to consult a number of online resources, such as encyclopedias.

If your topic comes from either the Apologetics or Mars Hill events, you’ll want to have a number of resources on hand to consult:

A good study or life application Bible.

A systematic theology text.

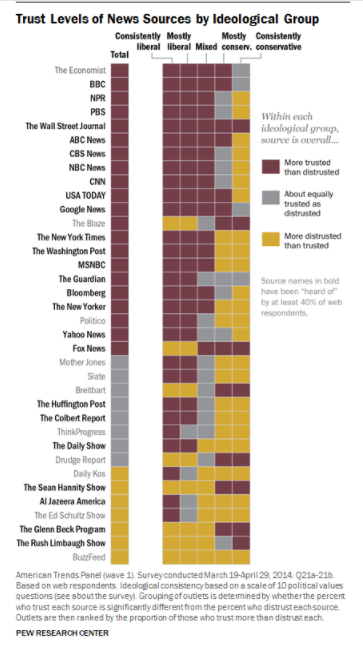

If your research topic is related to current events, you’ll likely want to consult a number of news sources online. Your best bets, in terms of credibility and even-handedness, will be The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, and BBC News. The Pew Research Center generated this useful infographic from research they conducted in 2014 regarding how trustworthy various news sources were perceived to be by various demographics.

In addition to these sources, LexisNexis is a powerful research database of exceptional quality. It’s normally prohibitively expensive to use, but if your family is registered with Stoa, you have the option of getting an annual subscription for only $40 per user per year.

Determining the Credibility of Sources

As you find each new source of information, it’s important for you to evaluate its credibility; that is, how likely is it that the source will give you truthful information? Answering that question is what the study of source criticism is all about, and it can be quite involved, depending on your particular research domain. Though there are a variety of methods used in the discipline, a straightforward and easy-to-remember one is the CRAAP test (I didn’t make up the name), as explained in this video:

Note

There are a handful of statements made by the speaker in the video above that generally tend to be true, but are not necessarily true, depending on the source and the particular topic at hand. Can you identify them?

For each letter in the acronym, you can ask a series of questions to gauge the credibility of the source.

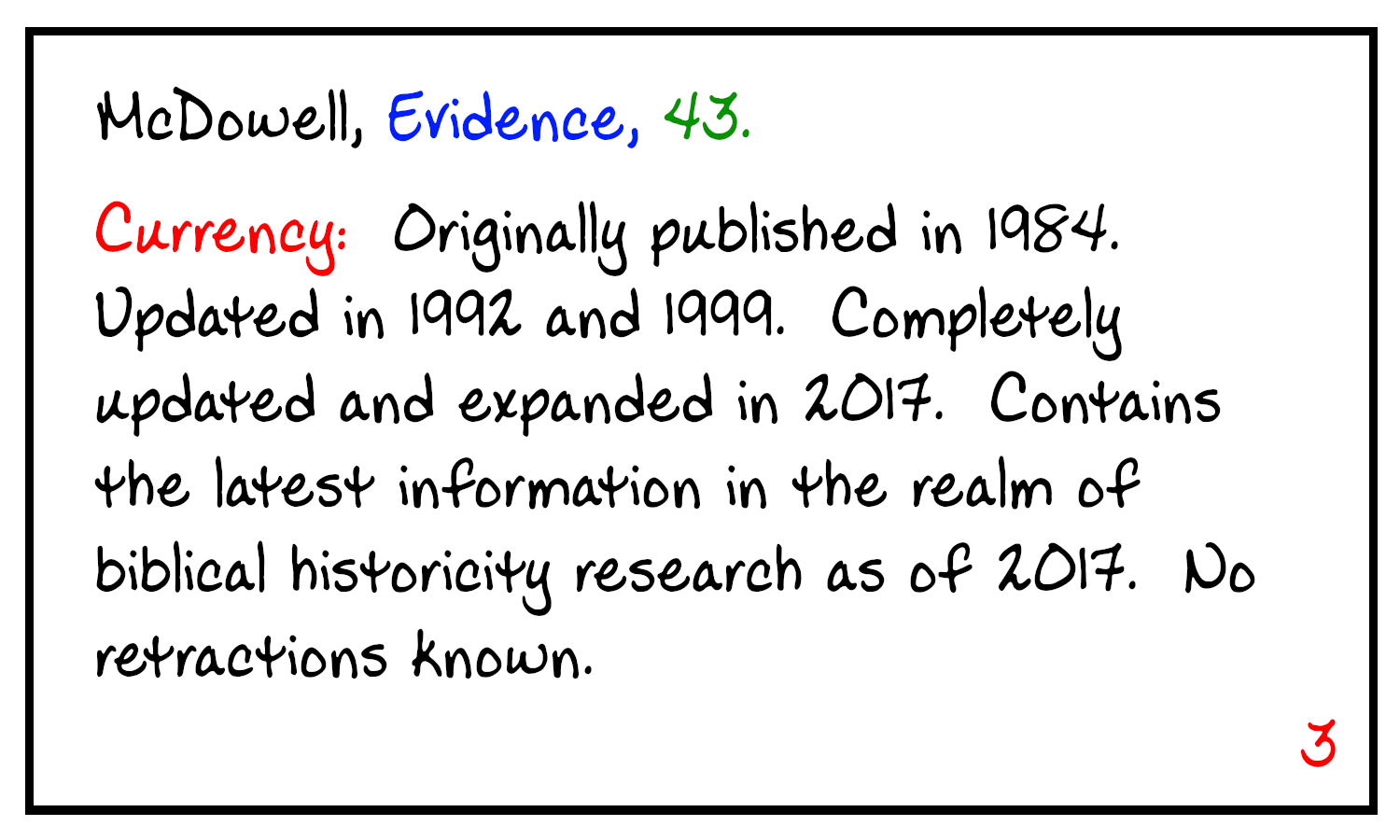

- Currency

How recent is the information? For subject matter that may be changing rapidly (e.g., current events), the more recent, the better, but this tends to matter less for subjects that are already well-established (e.g., history).

Have any updates been published? If new information came to light, and the author published an update, that shows they’re staying on top of the latest and greatest as the situation develops. If a substantial mistake was made in the initial publication, such that a correction or retraction was needed, that may indicate the authors may have made other mistakes.

- Relevance

How directly does the source speak to your topic? The more specific to your particular research question, the better; however, information that’s tangentially related to your topic may still be good to keep in mind for the broader context.

Are you the author’s intended audience? If not, the information may not be presented in an appropriate way, or at the right level, for you to benefit from it as much as possible.

- Authority

What is the source’s reputation? Authors, speakers, publishers, etc., that have a good track record of producing truthful content will be stronger sources than those with a tendency to make sensational or misleading claims.

Is the source qualified to speak on the topic? Those with expertise specific to your subject matter are more trustworthy than those considered experts in other fields, but lacking direct experience in your area of interest.

- Accuracy

Has the content been verified? Information that’s been through some sort of peer review process, and/or for which you can find corroborating evidence in other sources, is more trustworthy.

Does the author point to additional sources? A source transparently directing you to its sources, particularly if you’re pointed to raw data that you can analyze for yourself, is more credible than one that doesn’t.

- Purpose

Does the author intend to inform, opine, or persuade? An author’s motivations can give you clues as to whether or not their information requires a grain of salt.

Is the source objective? Biases of various sorts can slant a person’s presentation of information, so the more impartial, the better.

The strongest sources will be strong in all five of these areas, but that doesn’t mean you need to completely disregard a source that’s weak in one or two. If you do use a weaker source, it may be worth pointing out to your audience that you’re aware of the weaknesses (e.g., “This author exhibits significant bias in his writing, but his analysis of the underlying data appears to be sound.”).

Taking Notes

As you’re conducting your research, you’ll want to take good notes on everything you’re learning. What exactly should that look like, though? The process differs slightly depending on the kind of speech you’re preparing for.

For Platform Speeches

You start by collecting some supplies: a stack of index cards (either 3x5 or 4x6), and a handful of pens of differing colors. For each of the sources you consult, you’ll be assembling a deck of index cards.

The Citation Card

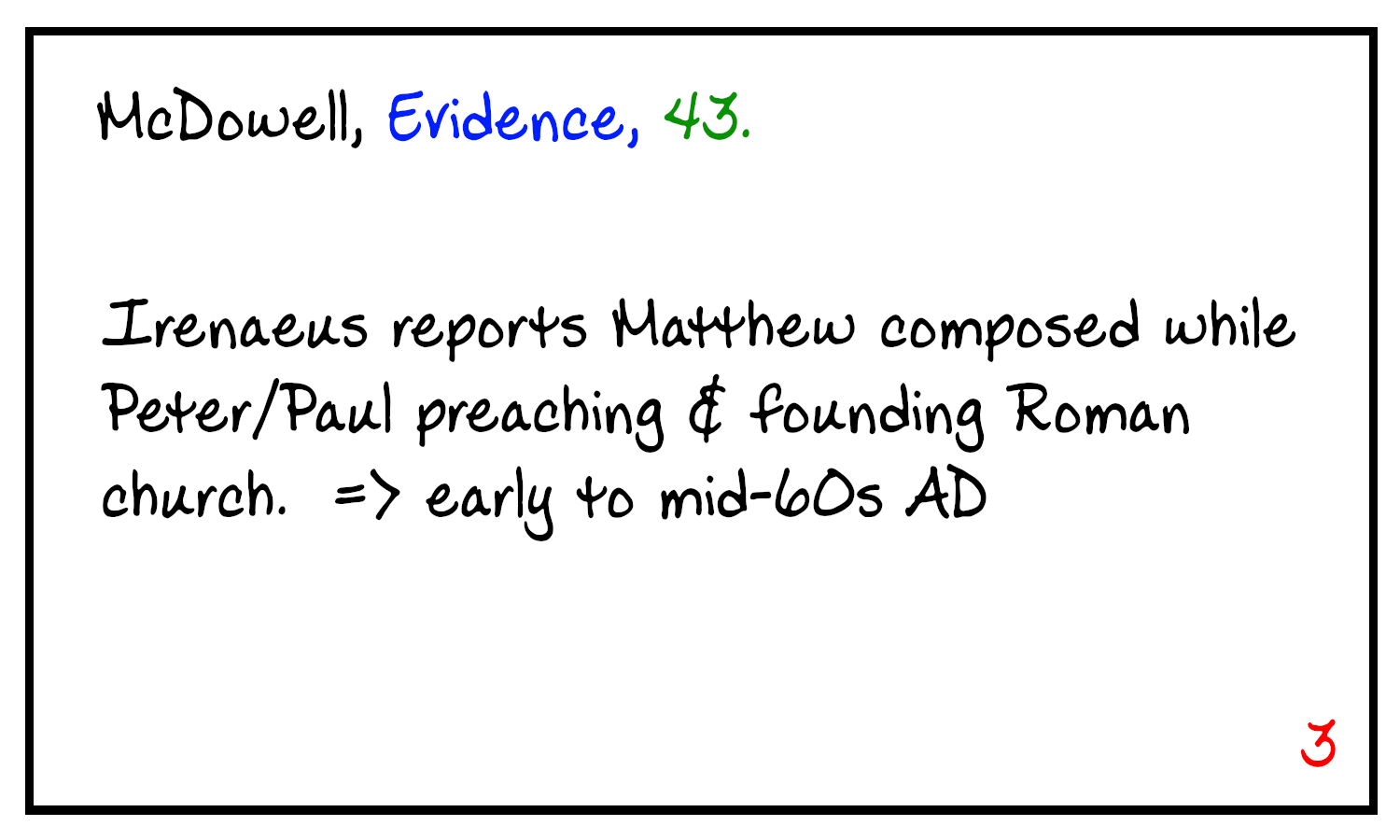

The top card in each deck will have the academic citation for the source on it. There are a variety of citation styles to choose from, and any one will really do just fine. That said, we recommend the Turabian style, so you’ll want to familiarize yourself with it. When writing up a citation card, it’ll be worthwhile to use different colors for the different parts of the citation (author, title, publisher, etc.), as this will make them easier to identify at a glance. In addition to the citation, you’ll also want to number this resource deck in the bottom-right corner of the card, so all your cards from your first souce will have a 1 in the corner, all the cards from your second source will have a 2, etc.

Credibility Cards

Before you dig too deep into a source, you’ll want to assess its credibility via the CRAAP test mentioned above. Create a card for each letter in the acronym. Start each of these cards with an abbreviated citation at the top:

Instead of using the full author information, use just the last name of the primary author.

Instead of the full title and subtitle, just use the first 1–3 words in the title.

Follow that up by the location of the information in the source (a page number in a print publication, section or paragraph number in an online article, time in an audio/video recording, etc.).

Be sure to use the same color scheme as on the citation card. Below the citation, write the word corresponding to the letter in the acronym, and then jot down notes to answer the questions associated with that element of the test. Be sure to include the deck number in the bottom-right as well.

Evidence Cards

As you read through a source, when you come across something noteworthy, you’ll want to capture that on an evidence card. Start such a card with an abbreviated citation at the top, and then below the citation, write a summary of whatever you found noteworthy. Be sure to capture the information in your own words, rather than simply copying (you don’t want to plagiarize, even accidentally). If there’s ever something particular that you want to quote verbatim, be sure to denote what is an exact quote and what isn’t. Finally, in the bottom-right corner, include the deck number as well.

For Limited Preparation Speeches and Debates

With Platform Speeches, the tendency is to have a small handful of sources, with a great many cards per source. With Limited Preparation Speeches or Debates, though, the tendency is to have a great many sources with only a small handful of cards per source. This isn’t a hard and fast rule—just how things tend to go. As such, cards for these events will look a little different from those shown above, having the following information:

- Tag

The tag is a brief (10 words or less) summary of what the evidence says. Think of it like a title for the evidence that follows. It needs to be short, sweet, and to the point, but also descriptive enough to help you differentiate it from your other pieces of evidence.

- Citation

After the tag, comes the citation, which you’re already familiar with from up above.

- Qualifications

In addition to the citation itself, it’s also highly recommended to have a sentence or two speaking to the qualifications of the source. We need to know where the information is coming from, for sure, but we also need to know why the source of the information is credible.

- Quote

Finally there’s the quote itself. This should be a word-for-word copy from the original source to your card of the information you want to have on hand. You probably want to shoot for roughly a paragraph or so, but how much information you copy will depend on what the quote is. You want enough information to ensure you get the point in context.